A masterpiece re-born

February 28, 2024 | Treasure tales and archive snippets | 6 minute read

In this post, we hear from Maria de Peverelli, Curator and Collections Manager at Holkham, as she shares how this pastel by Rosalba Carriera has been restored.

All images courtesy of Deborah Bates

One of the most rewarding aspects of my job is the opportunity to spend time with conservators, and through them to delve into an artist’s world through its materials and techniques, understanding the intricate process behind each work of art.

Over the past few months, I have been fortunate to witness firsthand the conservation journey of one of the masterpieces within Holkham’s collections: a pastel by Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757), an 18th-century Venetian artist renowned for her portraits capturing the essence of Europe’s elite. In this portrait she immortalized Edward, Viscount Coke (1719-1753), the only son of Thomas Coke.

The work portrays a youthful Edward during his Grand Tour. His countenance is captivating, exuding elegance as he meets the viewer’s gaze with a subdued yet profound expression, devoid of a smile on his delicate lips, yet rich in delicate nuances.

Just prior to his return to England, Edward was described as “sober as to wine” and possessing a “meek temper” by his father, who earnestly desired to marry him off to a lady of virtuous character who could shield him from the vices of the era. Looking at the young man’s features in Carriera’s portrait, one wouldn’t anticipate the grim turn Edward’s life would take. In 1748, Horace Walpole’s painted a starkly different picture: “Lord Coke has demolished himself very fast… always drunk, lost immense sums at play, and seldom returns home to his wife till eight in the morning.” Lord Coke’s descent into dissolution culminated in his childless death before his father.

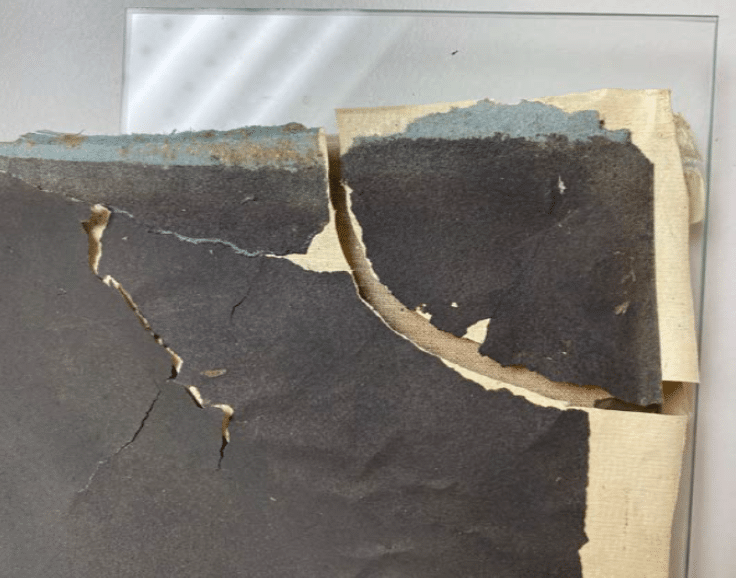

During my time at Holkham I have only seen the pastel in storage, its upper section covered by a curved black frame, concealing a damage that was considered irreparable.

Remarkably – as the image below clearly shows – the numerous tears in the background have miraculously left the figure untouched. The surface is nearly flawless revealing the artist’s extraordinary attention to detail, from the delicately rendered eyelashes to the subtle hues of the young man’s cheeks, from the texture of his attire down to the intricacies of his wig’s bow. The main structure “of the pastel” also remains intact, with its original strainer and wood backboard preserved.

The pastel in July 2022

It is the upper top and left sections of the sheet that bore significant damage, marked by cracks, losses, and planar distortion. This deterioration was aggravated by a misguided restoration attempt where a heavy, incompatible, paper was affixed to the primary sheet’s verso. The disparity in paper strength, coupled with environmental changes over time, resulted in tension, leading to buckling, creases, and planar distortion. As a result, additional cracks have emerged or worsened, reducing the pastel to a desperate state.

For years, the daunting challenge of restoring it remained unaddressed.

The turning point for the artwork came in the spring of 2023 when Xavier Salomon, Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the Frick Museum, visited Holkham to inspect the Rosalba Carriera works in Holkham’s collection for his forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the artist’s oeuvre.

Despite concerns about the portrait’s condition, Salomon recognized the exceptional quality of the figure and recommended contacting Deborah Bates, the only person in the UK he deemed capable of tackling such a hard restoration challenge.

The pastel was brought to Bates in the early Summer of 2023.

Deborah’s preliminary examination revealed other minor conservation issues such as pitting in the face, a scratch across the subject’s forehead, and some surface water-staining and mould.

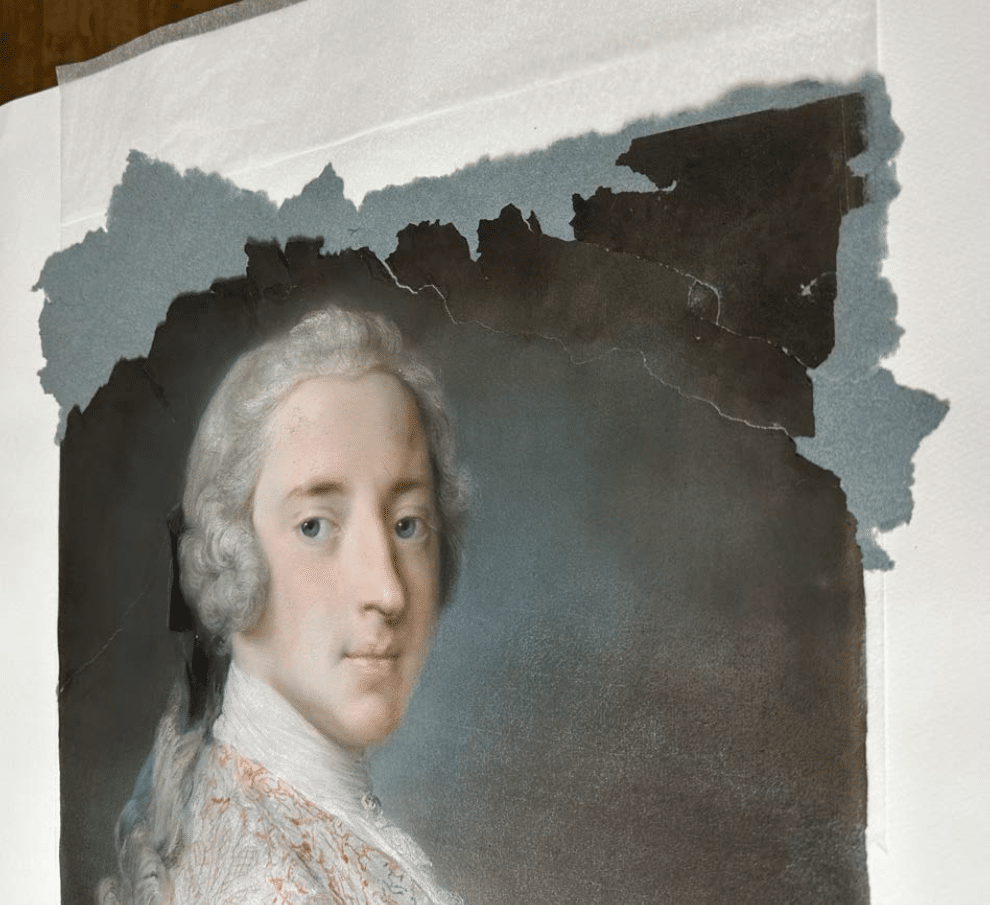

She then requested a meeting: Xavier and I travelled to Kent in July 2023 to meet with her, and, after consultation with Lord Leicester, it was decided that the first step would involve detaching the upper right corner, which was already separated from the rest of the sheet, to test the feasibility of separating the primary sheet from the “repair” paper.

Corner detachment to enable testing

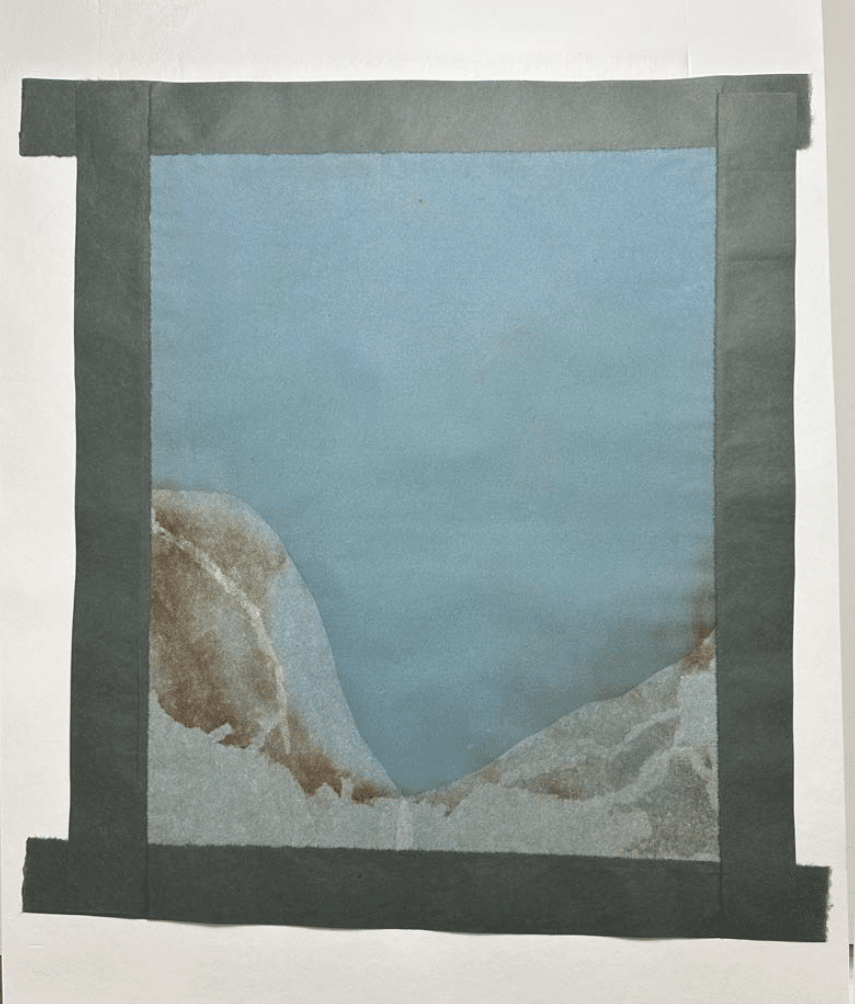

Having assessed the possibility of a treatment, Deborah commenced the restoration process by separating the primary support of tinted blue pastel paper from the linen-covered wooden strainer, preserving the return of blue paper and the original nails in situ. The stretcher was then cleaned before being covered with a thin sheet of acid-free museum board.

Next, tests were conducted to assess the feasibility of removing the old repair paper from the verso of the sheet. While a chemical solvent was employed to release the tissue and paper on both recto and verso, the removal of the repair paper itself necessitated dry mechanical processes, slow and nerve-racking. In areas of severe damage, portions were retained for reintegration wherever possible. When reintegration wasn’t feasible, fragments were preserved for the purpose of creating matching repair paper.

Assembly of parts during removal of old repair paper

Mould on the recto was removed, followed by fumigation of the entire piece.

Tears were repaired and the remaining losses were infilled with matching paper, crafted by pulping a congenial repair paper with the original sheet fragments mentioned earlier. To reinforce the repair work, a very thin lens tissue was applied to the verso.

Consolidation of larger fragments begins; infilling with matching paper

To address planar distortion, the primary support underwent light humidification from the verso, targeting both local and overall distortion.

False borders made of tinted Japanese repair paper were applied to the edges of the verso. The entire piece was then re-attached to the prepared strainer by adhering the false borders.

Verso with lens tissue support and false margins

Recto repairs were then meticulously retouched with matching pastel, resulting in an outstanding restoration.

This remarkable transformation complete, the next endeavours will be finding a suitable frame for this exquisite pastel and securing for it a pride of place within the Hall that it deserves.