Creating the Cosmographia collection database

July 25, 2024 | Treasure tales and archive snippets | 5 minute read

Within the South Tribune of Holkham Hall is an extraordinary collection of books stretching across 113 volumes, known at the Cosmographia. As a Hall Guide, Jo Bannister regularly discusses the books with visitors. When an opportunity to work on a project transferring data and images relating to the Cosmographia onto the Holkham Collection Database arose, she jumped at the chance, as she explains here…

Compiled by John Innys (c.1695-1778) and sold to Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester, in the 1750s, the Comographia is a bound collection of engravings and wood block prints of maps, architectural plans, interesting landmarks, and key historical events. Innys was a bookseller and had collected the images from the various volumes that had passed through his shop. As such, a large number of the maps inside the Cosmographia have text on the reverse showing exactly which book he had removed them from. The prints were bound together into geographical areas, and then each volume has a handwritten ‘contents’ page listing which counties and towns feature.

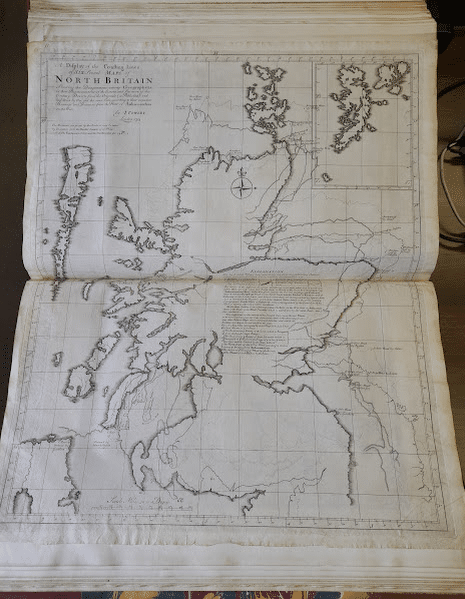

The volumes covering the British Isles are the most numerous, and the ability of those in the eighteenth century to compare maps drawn by various cartographers highlight the difficulty in undertaking this task. This map of Scotland, compiled by John Lodge Cowley in 1734, clearly shows the concern that maps may not be accurate, and the risk in relying on them. Although a cartographer himself, what Cowley created here is a compilation of six different maps of Scotland, laid one onto another, demonstrating the vast differences in coastline and location of towns.

CN. 96.88 – A display of the coasting lines of six several maps of North Britain shewing the disagreement among geographers in their representations of the extent, and situation of the country. Drawn from the originals (as published). John Lodge Cowley.

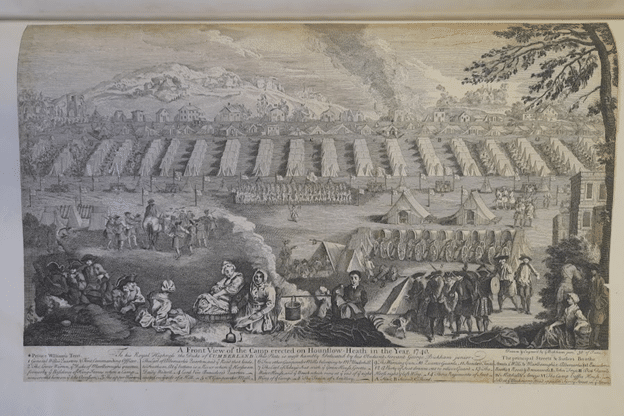

The Cosmographia does not just contain images of physical places and locations, historical events are portrayed as well. This image by George Bickham Junior shows A Front View of the Camp Erected on Hounslow Heath in the Year 1740. A key across the bottom draws attention to the areas of interest on the engraving, including Prince William’s Tent (William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland), and The Camp Coffee House.

CN. 83.128 – A front view of the camp erected on Hounslow Heath in the year 1740. George Bickham (Junior)

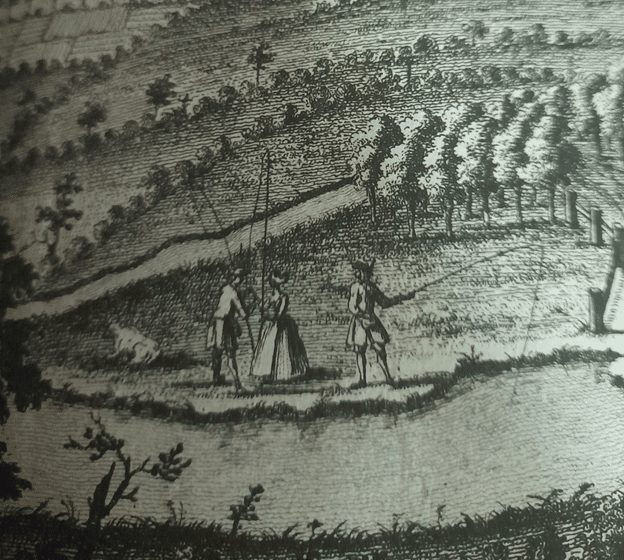

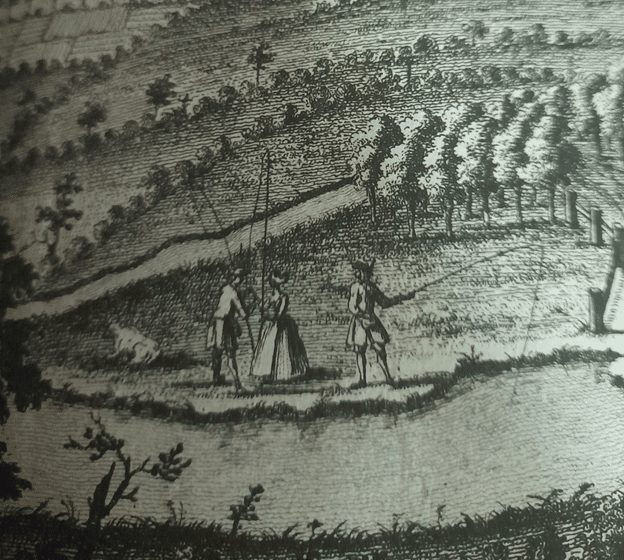

Whilst the images are breathtaking, and the level of geographical knowledge going into the creation of maps and birds eye views without being able to fly over the area is outstanding; the part I love to look at in these engravings is the detail of the people, simply going about their business.

This close up is from The East Prospect of Birmingham, and shows a trio enjoying a fishing trip by the river.

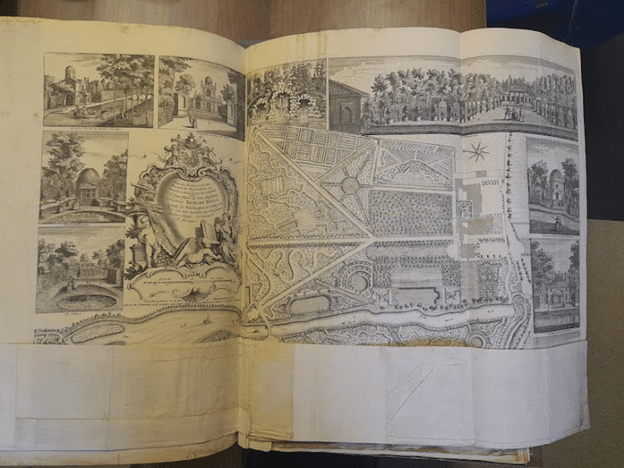

One of the questions most asked by visitors when discussing the Cosmographia is ‘what was it used for?’. Some of the houses featured, especially those connected with the higher levels of society at the time, are represented more than once, with two or three artists and engravers portrayals on subsequent leaves. As a student of architecture, I am sure Thomas Coke would have enjoyed studying these closely, to see which elements one artist highlighted over that of another, and comparing the various viewpoints. While a lot of the pages show little evidence of use, the folds still fresh and crisp and the pages white, some have clearly been regularly consulted. (In fact, the whole series was rebound in the 19th century which suggests that there was substantial use to warrant such expense). One of the pages showing the greatest use is that of a plan of Chiswick House by John Roque in 1736. Chiswick House was the home of Lord Burlington, a friend of Thomas Coke. Although I can be accused of having rather a sentimental mind, I can easily see Thomas opening and studying the engraving whilst recalling conversations with Burlingham and William Kent about the ideal Palladian style of house, and desired layout for a grand estate.

Each time the map has been opened and examined the paper has weakened, the picture below shows that there are historical attempts at repair and reinforcement of the folds along the bottom edge. Frustrating as it is to not be able to see the whole engraving, our focus now is on preserving and protecting the original as much as possible.

CN. 83.115 – Plan of Chiswick House:[Plan du jardin & vuë des Maisons de Chiswick sur la Tamise a deux lieves de Londres. John Roque