Holkham Dinner Party – The Architecture of Dining

June 9, 2020 | Holkhome | 4 minute read

Although its grand rooms have for the past few weeks been shuttered, Holkham Hall has over the course of its history played host to a number of grand dinners. Whether catering to five or five-hundred, these dinners were designed to impress guests with the wealth and taste of the Coke family.

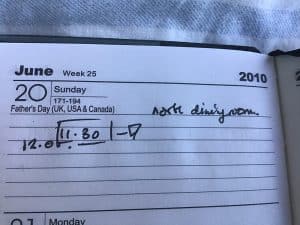

All good shows need a stage, and the stage for dining at Holkham was primarily the North State Dining Room (see image above). Architecturally, it is a perfect cube, the space further elongated through a domed ceiling, which makes the room feel much larger.

The room is further enlarged through what was known as a buffet niche – not, as we would think today, where a selection of tasty tapas was laid out! Instead this was a place to display some of the family’s wealth, typically, this would include a display of silver, though at Holkham they did things slightly differently. Instead, the niche was filled with a very large, red porphyry table with a green marble top. The household accounts record that the table top was sent from Rome in 1754, whilst the supports are taken from a sarcophagus, also sent from Rome, by the architect William Kent in 1718. Underneath the table is a large, granite wine cistern; this had sentimental value for Thomas Coke, the builder of the hall, as it was a wedding present, given to him by Lord Edgcumbe.

Table and cistern

Table and cistern – details

The room has two fireplaces – one on both the east and west walls, visually balancing the buffet niche on the south wall. As well as conforming to the symmetrical designs favoured in the eighteenth-century, including two fireplaces in the room’s design has a practical role – having worked in this room in the bleak mid-winter, it can be a very chilly place to be! Two fireplaces would therefore provide extra warmth and comfort for the dinner guests.

The fireplaces are decorated with marble slabs depicting two of Aesop’s fables: the Bear and the Beehive and the Sow and the Wolf. The pig in the Sow and the Wolf has lost her snout; this damage is historic, and was noted by Arthur Young in 1769. The designs were adapted from Francis Barlow’s lavishly illustrated edition of Aesop’s Fables, published in 1666, a copy of which was owned by Thomas Coke – we recently had it conserved, as the binding had disintegrated through heavy use, first by masons copying the designs, and then by scholars of the architecture of the hall.

Detail of broken snout

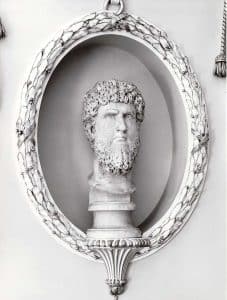

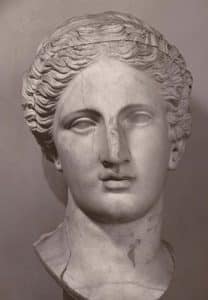

Above the fireplaces are two gigantic antique heads – one bought as the gluttonous emperor Lucius Verus (actually depicting his father, the more temperate Aelius Verus), and the other, the virtuous goddess Juno. The two coloured busts also seen in this room are similarly paired – this time we have the bad emperor Caracalla and the good emperor Marcus Aurelius. Thomas Coke regularly employed the technique of placing works of art with contradictory meanings opposite one another. In doing so, he demonstrated the extent of his learning, and that he understood the underlying message of each work that he owned.

Aelius Verus

Juno

View all latest blog posts here.

Back to Journal Back to Journal