The gardener meets a marketing genius

December 16, 2020 | Garden goss | 7 minute read

Don’t ever think that archives are just places where dusty old documents are kept. They are full of moments in history that are waiting to be explored. It is vital to remember that for a document to have been kept for decades, sometimes centuries it must have been important at one point. The archives at Holkham are full of just such documents some of which are well-known, and others are just waiting to be explored.

Earlier this year I had the pleasurable experience of sharing one of the archive’s most well-known documents with Mark Morrell, head gardener at Holkham. He knew all about its creator and its purpose but, but it was quite another thing to be turning the pages of such an important volume: a Humphry Repton Red Book. Its reputation had been made over 200 years ago and still attracts attention in 2020.

The Red Book is a small landscape volume, slightly larger than A5 and surprisingly has an orange coloured binding, made of Morocco leather. It was the first ever Red Book produced by local landscape designer Humphry Repton and as such has huge historical significance in the history of the Red Book on which he was to make his reputation. But who was Humphry Repton what makes the Red Books so interesting to so many people?

The land immediately around Holkham Hall had changed significantly in the eighteenth century. Firstly, when Thomas Coke returned to Holkham in 1720s, there was a period of great upheaval as roads were taken up and slopes, lawns and gravel walks were created, and large numbers of trees planted in formal arrangements as designed with William Kent and others. This was followed, after Thomas’s death, by his widow, the remarkable Margaret, who employed Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown to oversee modernisation which lasted three years. It is likely that Brown toned down much of the formality that had been enjoyed for the previous 40 years. Instead, a more natural-looking parkland emerged. Similarly, after the estate had been inherited by Thomas William Coke (Coke of Norfolk) the fashions in landscapes had changed and after a period of focus elsewhere on the estate, a new designer was sought: Humphry Repton.

Repton originally came from Bury St Edmunds and was educated there and in Norwich. His interest in gardening probably developed when he was travelling and learning about the mercantile trade in low countries and Germany. He was an apprenticed in 1768 to the textile industry which was booming at this point in Norwich, however his interests lay elsewhere. Within ten years he was married and following the death of his parents he was living the life of a country gentleman on the Felbrigg estate, owned by the prominent whig, William Windham. He was able to indulge in drawing, writing, and reading volumes from Windham’s library. This idyllic lifestyle could not to last and after a spell in Ireland working as a secretary for Windham he moved to Essex and launched himself as landscape gardener. He used his whig connections to create a large client base across the country.

Repton differed from previous landscape designers such as Capability Brown. He took no part in the physical work, he was purely the ideas. He created the vision, the dream, and a means to create it by preparing each client their own ‘Red Book’. The ‘Red Book’ contained maps, illustrations and explanations carefully written to inspire the clients to want to create the vision of paradise he was selling. The ultimate marketing tool was the ‘before’ and ‘after’ views showing how the landscape could be improved with his ideas. The handsome volumes he produced could be used as a basis of redevelopment, showing the agent exactly what the designer wanted, or it could be left in the library for visitors to peruse and aspire to. In total Repton produced over 300 ‘red books’ for estates across the country. Sometimes clients had no intention of creating his vision rather they wanted their own Red Book as a status symbol and to show political alliance. Notable sites include Woburn Abbey, Brighton Pavilion and, a little closer to Holkham, Sheringham Park.

His first ‘Red Book’ written for Holkham, uses these devices of ‘plans, hints and sketches’ for the creation of pleasure gardens land near the lake. It is interesting to note that the volume is addressed not to Thomas Coke, but rather Mrs Coke, his wife. Repton described in his introduction the ‘magnificence’ that Holkham possessed: ‘a vast expanse of lawn, an immense sheet of water, and woods…too large for painting to express’. This language he is using is suggesting a very picturesque setting rather than setting the basic facts of the idea.

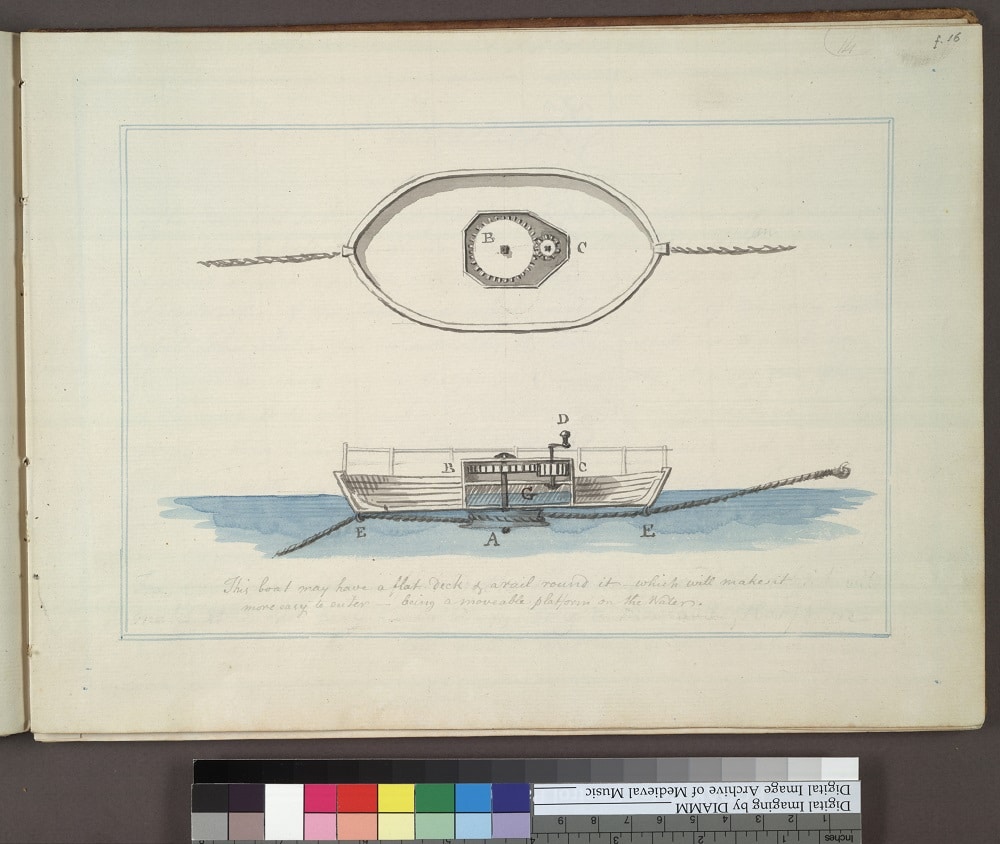

Repton wanted to build on the redevelopment of the lake already undertaken by Coke and his suggested a walk along the eastern edge of the lake, leading to a boathouse, where he proposed ‘an elegant pavilion’, and on through a tunnel, completely covered with creeping plants, from where the walker could divert onto an upper path: ‘this sort of surprise…will appear a perfect wonder in Norfolk’.

Given that Repton addressed the volume to Mrs Coke, it is appropriate that he includes a ferry, ‘so contrived as to be navigated with the greatest ease by any lady’, which was to link this shore with the opposite side of the lake, where the effect was to be ‘rural but not neglected’. Here he proposed to build a thatched cottage in the woods, modelled on a Severn fishing hut, and so ‘being unlike the usual cottages in Norfolk, it will appear the habitation of industry with an affectation, rather than the reality of penury’. Further walks would lead to a ‘romantically bold’ chalk pit, which would be ‘a scene of pleasing gloom’, and southwards to the stables or northwards to the church.

What makes the Red Book for Holkham so precious is that in the intervening 200+ years there have been further changes and developments in the park immediately around the house, therefore there is little evidence either on the ground to his direct influence. Interestingly, there is little evidence in the Holkham archives to suggest that show that the ambitious plan was completed. Normally, it would be a case of checking in the account books for details of payments made to for particular projects- but in this case there are few references. In 1802, payment is recorded for gravel walks on the west side of the lake, and the building of a ‘subterranwous passage leading to garden’ which was possibly the creeper covered tunnel Repton proposes. But this is some 13 years after Repton had presented Mrs Coke with the volume – perhaps it was a later, adapted plan with it’s origins in what Repton had suggested? We still don’t know exactly what was built from the Red Book at Holkham, but as Mark can testify, handling something of such historical importance is a great thrill.

View all latest blog posts here.

Back to Journal Back to Journal