Uncovering new sources for the history of Holkham

January 17, 2024 | Treasure tales and archive snippets | 6 minute read

Holkham Archivist Lucy Purvis was recently given an archival treasure which we didn’t know existed. Let’s take a look at what is is!

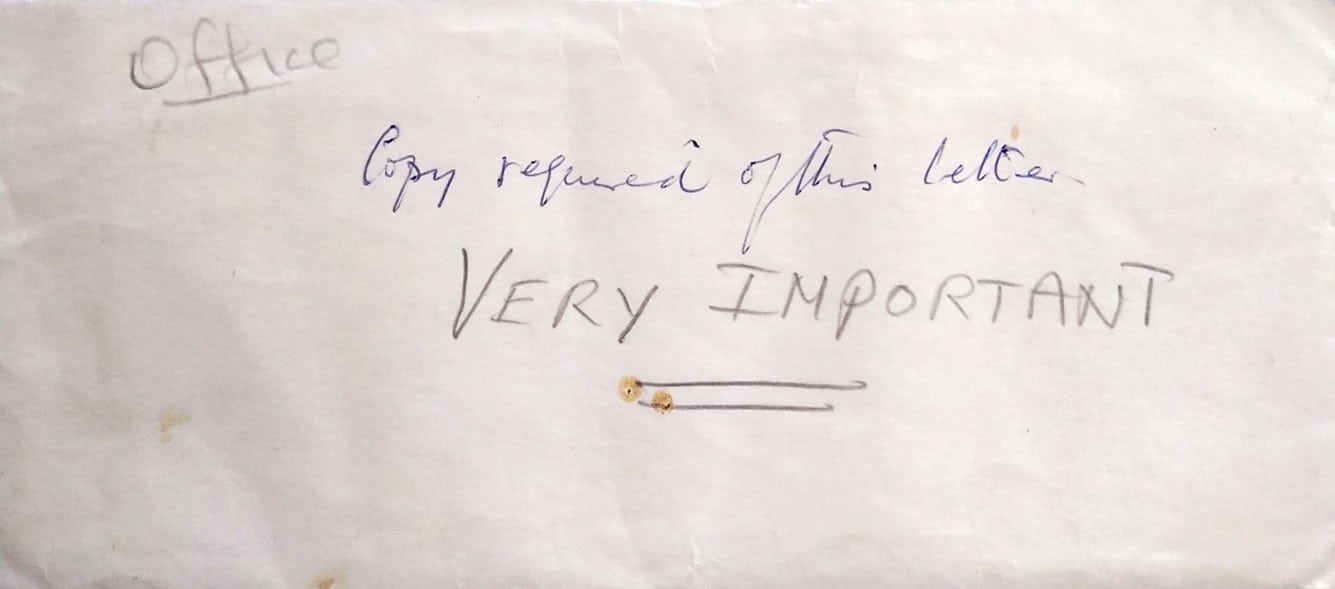

Being the archivist of a great estate like Holkham is always fascinating, and I particularly enjoy unearthing archival treasures which may have lain languishing in a drawer or cupboard. Recently I was handed such a document. As you can see, from the accompanying envelope, someone had deemed important but for unknown reasons it never found its way to the Archive.

Inside the envelope lay a substantial letter written between a father and son, very significant to both the history of the hall and the collections which he helped to amass. To say I was excited, was putting it very mildly, this letter could perhaps inform historians and academics to develop a new narrative for Holkham.

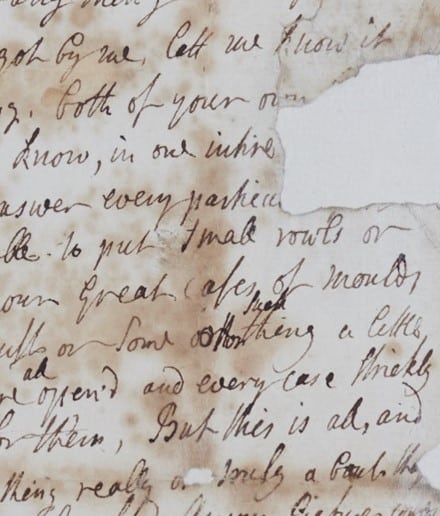

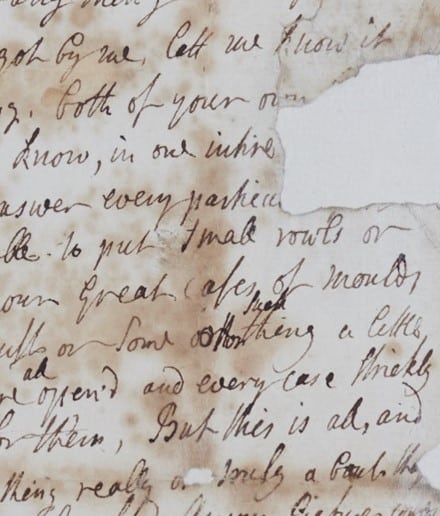

Before I could study the letter, it was essential to have it conserved. There were significant losses and an unfortunate stain that meant parts were illegible. The paper conservator was able to repair and strengthen the document. The infilled spaces ensure no further words can be lost, but it’s frustrating that the full text will never be known, however by reading between the lines it is possible to get the gist.

This letter, dated June 1753, was sent by the builder of Holkham Hall, Matthew Brettingham to his son, Matthew Brettingham who was based near the Spanish Square in Rome. Matthew Brettingham Jnr had been acting as an agent for Thomas Coke, and others, since 1747, buying ancient marbles, replica plaster casts and paintings to fill gaps in the Temple to the Arts, a.k.a. Holkham, that was being built by his father. The letter initially begins with references to pictures and moulds purchased for Lord Anson to be shipped to London on board the Britannica. The Brettinghams had realized the commercial benefit of making and acquiring moulds of key ancient statues which could be used to make many casts that could be sold to collectors at home.

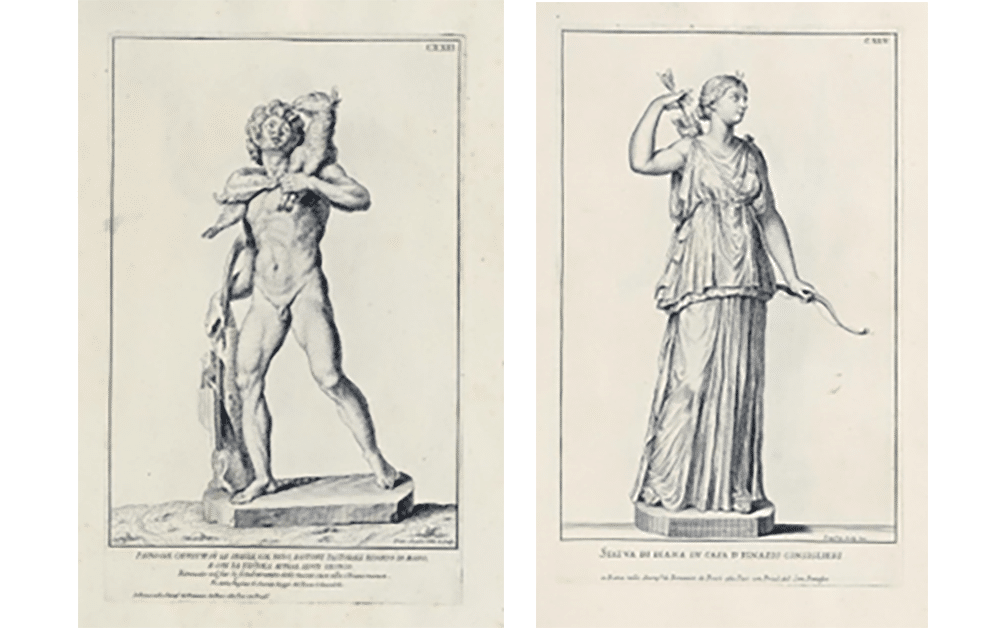

Matthew suggests to his son that he should be looking for another ‘drapery figure’ mould to be a ‘companion to your faun with a goat upon his shoulder’. He had bought the faun mould from the Odescalchi collection, knowing that it was a great sculpture: this marble had been included in Raccolta di Staue Antiche e Moderne – a catalogue of the very best classical, renaissance, and baroque sculptures in Italy published in 1704. Incidentally, this book was very familiar to Thomas Coke, and he likely consulted it prior to his tricky acquisition on his grand tour of Diana.

Perhaps the mould for Urania would have fitted Matthew’s suggestion of a ‘drapery figure’? This was bought after May 1754 and later Brettingham sold a cast to Lord Leicester for £10, and another was made for Kedleston at a cost of £8.

The placing of the ancient marbles in Statue Gallery and around the house has often intrigued me and this letter sheds some new light. It discusses changes to Lord Leicester’s original bold plan which was to include a statue of himself in the Statue Gallery, carved either in Rome or London. Instead, Brettingham informs his son that he, Lord Leicester, plans to put Diana in the niche over the chimney. However, when looking at that niche today, it hard to imagine the mighty Diana in that spot – Diana’s height is 186 cm, whereas Apollo is only 164 cm.

There is also reference to ‘two bustos with parti-coloured drapery as mentioned in his lordships letter to you’. Brettingham advises Matthew not to buy these having ‘alterd our scheme about them’. Perhaps, these two would have been a pair to complement the portraits of Caracalla and Marcus Aurelius, which also have later busts of variegated marble in the North Dining Room, the latter was purchased by Matthew in July 1752. It’s interesting to note just how fluid the plans for the decoration and placement of items was at this late stage in the construction of Holkham Hall.

Brettingham’s final request is for Matthew to find ‘two of three good casts of the Venus of Medici’ for Lord Leicester. There are two casts of Venus at Holkham, firstly in the Marble Hall and the instantly recognizable Venus de Medici in the Small Statue Corridor leading to Strangers’ Wing; both of which were supplied by Matthew.

The letter concludes with details of shipping the statues, casts, busts and artwork, and suggests that they should go to London and not Yarmouth as they (presumably the customs and revenues collectors) are ‘not being acquainted with the nature of things sent by you,’ and ‘may value them higher than they really are worth’. The business that the two of them had set up, supplying a selection of casts chosen from Italy to discernable collectors could have made their fortune, but unfortunately, few commissions came from the casts. They can mostly be found in houses where Brettingham senior was the architect, for example at Kedleston and Richmond House.

In a previous letter it is clear that Matthew, who famously walked from Rome to Naples, had suggested taking a trip with a companion further east to explore ‘Egypt, Asia and Greec’ and how it would be develop himself however his father’s position on this proposition is clear ‘By no means think of it, it not being your business to consume your time after chimeras of young traveling gentry’!’ Instead Brettingham suggests Matthew should focus on his business at home!

It will be interesting to connect the loose ends in this letter with other known correspondence between the father and son, and then analysing at the details together with a small account book of used by Matthew Brettingham and see what further information can be deduced!

Lucy Purvis

Archivist, Jan. 2024

Back to Journal Back to Journal